Sharing Findings and Presenting Evidence

Faculty who do inquiry into their students’ learning find that sharing their work, at all stages, is crucially important. “Going public” (even in very informal ways) not only provides an audience for one’s inquiry about teaching practice and student learning, it also often helps clarify for the faculty investigator what she or he really knows or is discovering.

Sharing one’s questions and findings can take many forms, from brown bag discussions with colleagues to formal conference presentations. Increasingly, sharing can also take the form of digital presentations of one’s work, such as the cases presented in Windows on Learning. Irrespective of setting and relative formality, going public with one’s inquiry is a critical way to deepen and extend one’s work.

Ways of Telling and Showing in Digital Spaces

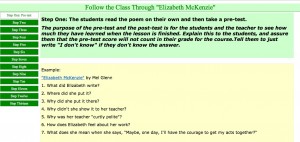

Within the Windows on Learning site alone there is a rich variety of methods for telling the stories of effective and innovative teaching practice within the context of the complexities of student learning. Nancy Ybarra (Los Medanos), for example, chooses to share her use of Reading Apprenticeship strategies in the classroom as the exemplary story of a single class period.

Annie Agard (Laney College), who has taken on the challenge of teaching poetry to her ESL students, lays out an entire sequence step by step, complete with video of her teaching and her students’ learning at every stage.

At Glendale, a team of faculty using an innovative approach to technology in the writing classroom not only tell the story of their innovation but also share their methods for studying their practice. One result of this is a presentation of the many ways they “capture” student learning and thinking, including screen capture, think alouds, “roving capture” (moving around the classroom), interviews, and group work.

Other faculty in Windows on Learning present their work as a sequence: question, initial analysis or data gathering, intervention, and finally results. Katie Hern (Chabot College) and Jay Cho, Brock Klein, Ann Davis, and Carol Curtis (Pasadena City College) are good examples of this way of telling and showing.

One of the most important effects of Faculty Inquiry is helping to make student learning visible. Whether the approach is to track student trajectories across an entire semester (Glendale) or collect the work of a few student cases and present all of their work as a body of evidence in support of a method, (David Reynolds of West Hills), it is a vital part of these representations to help other colleagues see students and their learning more clearly.

Navigate to other pages in the Faculty Inquiry Cycle:

- Developing a question

- Designing a plan for research

- Gathering and evaluating evidence

- Presenting and reviewing findings

August 20, 2008